Please choose your photo size from the drop down menu below.

If you wish your photo to be framed please select Yes.

Note: 16″x 20″not available in a frame.

Images can also be added to accessories. To order please follow these links

£8.95 – £49.95

Please choose your photo size from the drop down menu below.

If you wish your photo to be framed please select Yes.

Note: 16″x 20″not available in a frame.

Images can also be added to accessories. To order please follow these links

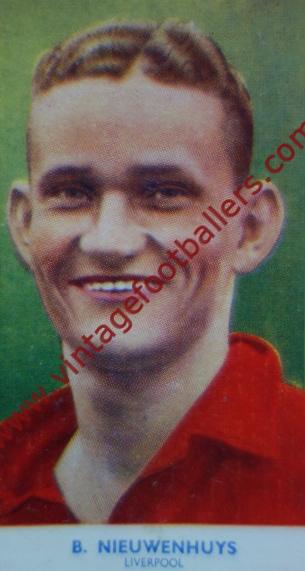

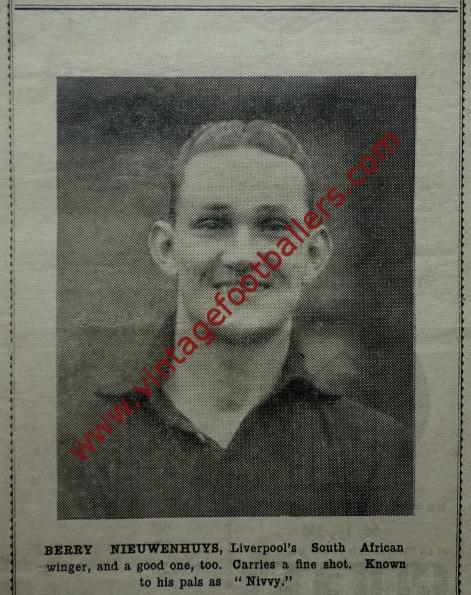

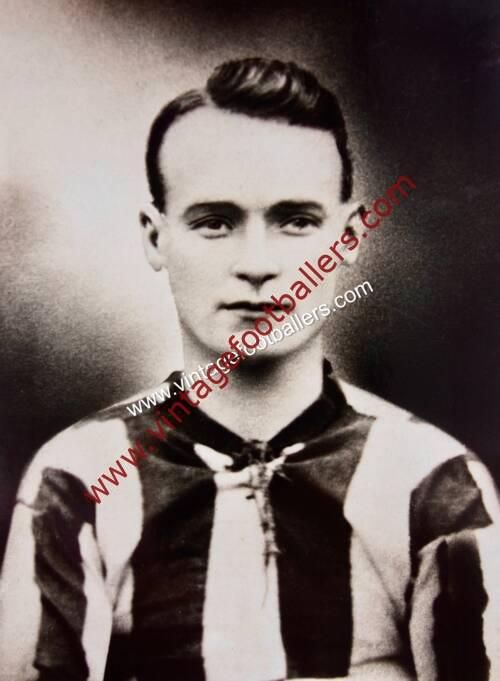

Winger Berry “Nivvy” Nieuwenhuys was born on 5th November 1911 in Kroonstad in the Free State, and after completing his schooling at Bethlehem went to work in the mines in the Transvaal. A keen and natural sportsman, his first love was rugby, but he soon switched to football, playing for Boksburg in 1931 and Germiston Callies in 1932. Imagine this. You’re a relative youngster playing a minor club game of football in South Africa when a man dashes onto the field during a lull in play and asks if you’d like to play for Liverpool. You wonder if he’s for real, but, of course, accept. A few weeks later, on the other side of the world, you are playing in front of 50,000 plus screaming spectators at Anfield. It sounds like something out of Boys Own magazine or the Beano annual, but that’s just what happened to Berry Nieuwenhuys in 1933. Eight years earlier another young South African player, Arthur Riley, had gone across to England to keep goal for Liverpool Football Club. His English-born father still lived in South Africa, where he keenly followed the sport. Having been impressed by Nieuwenhuys and another player, Lance Carr, he contacted the management at Liverpool and told them that he’d found a couple of “likely lads” in South Africa. The Brits told him to go ahead and hire them. That was the way people did business in those days – no agents, no contracts, no fat commissions; just a shake of the hand.

The eager Nieuwenhuys and Carr arrived in England on 11th September 1933 and were met on the quayside by Walter Cartwright and George Patterson, Liverpool Football Club’s Chairman and Secretary-Manager respectively. After one warm-up game in a junior side Nieuwenhuys was named for the senior side to play against Tottenham Hotspur at White Hart Lane on 23rd September. The Evening Express headlines told it all. “A gem from South Africa” they trumpeted. “Nivvy’s triumph in first big match for Liverpool. Home defeat for Spurs after 2 years.” The English had trouble with his full name and immediately shortened it to something more handy; “Nivvy” as “the typewriter won’t stand the strain of spelling his name in full.” The South African had battled with a wet ball and unfamiliar slippery grass at the Lane in the first half, but in the second he gained confidence and set up two brilliant goals for his new club. Nivvy’s second game was no less than a Merseyside derby at Anfield. He opened the scoring after roughly half an hour’s play in a “cool and calculating manner” in the best derby for 30 years according to the Evening Express. The local papers were full of praise for the newcomer: “’Nivvy’ afterwards showed that he has the big game temperament, but he has more – the ability. He moved about smoothly, employed touches of the master craftsman, and his centres were ever thoughtful. He certainly captured the fancy of the ‘Koppites’. He is neatness personified. By no means an individualist, he adopts the easiest path, making some delightful short passes along the ground to his inside partner and next turning over a choice centre. “Nivvy” is anything but flashy, but he has a wonderful turn of speed.”

Nieuwenhuys was interviewed by the Evening Express following the game and he was thrilled to have taken part in “the greatest match in which I have ever had the honour to play.” “Never before had I seen such a vast crowd, such brilliant football, or such clean football, and it was the thrill of my life when I managed to score the first goal. The point which struck me most was the cleanliness of the game. When we were leaving for England we were told that the game here was rough and dirty. Well, I can assure you that this match was 100 per cent cleaner that anything I have seen in Africa. I did not see one real foul in the entire ninety minutes. I confess I was rather staggered by the size of the crowd at the start but I did my best to forget they were there. That was hard in view of the continuous roar of voices. Still you could play in front of a crowd like that for years. They are such sportsmen. I thank them for the encouragement they gave me and also for the wonderful reception I was accorded when I left the field. I don’t mind confessing it touched me.”

“It’s Our Nivvy, our British Nivvy”, the Liverpool fans sung, convinced that their favourite should play for England, and numerous football writers declared the fleet-footed player to be the best winger in the land. Not only was Nivvy a brilliant right-wing, but he could fit into any position without effort, being one of a select few to play in nine different positions in top-level football. The two positions he never filled – left-wing and goalkeeper – he was quietly confident would not pose a problem if the need arose. But it was not to be. The rules stated that for a player from the Commonwealth to represent England his father had to have been born in the UK, as in the instance of Gordon Hodgson, and this was not the case with Nivvy. The debate was, however, shortened by the unwelcome arrival of Hitler in Poland in September 1939. During the War years Nivvy served as a PT instructor with the Royal Air Force, captaining the RAF side and still managed to play numerous wartime games for Liverpool. Footballers usually represented the clubs nearest the camps where they were based and Nivvy played for West Ham in the early 40’s, scoring 3 times in 16 wartime appearances, and he also played for Arsenal in 1945-46.

One thing that didn’t come with the fame was the obscene wealth associated with modern football. After Nivvy had given Liverpool five years’ staunch service, the club rewarded him with a benefit match against Everton from which he received the princely sum of £658. During the War things were even less rewarding – players were paid with sweets and cigarettes. Nivvy, a lifelong teetotaller and non-smoker, used to hang onto his sweets and swap his cigarettes for even more delicacies. When hostilities ceased Nivvy and his Liverpool teammates travelled to the USA to promote the game in that country. They played ten games and won all ten, with 70 goals for and just ten against, in front of a total in the excess of 100,000 spectators. The players’ earnings? Just £6 per game and a £2 bonus for each match they won – a gross earning of £80 per player for the trip.

Nivvy turned 35 in the first post-war season, 1946-47. He played the first seven games of the campaign and then featured again in eight in the middle of the successful season in which Liverpool won the League Championship, contributing 5 goals to the campaign. By then he had scored 79 goals in 260 appearances for The Reds and he also scored 64 goals in 136 Wartime matches. He retired from football in 1948, returning to South Africa to take up a position as assistant coach to golf legend Bobby Locke. In 1946 Nivvy had entered the British Open after hurrying back from Liverpool’s tour of the USA, and missed the cut by just two strokes. That same year he played in the Irish Open, figuring amongst the money winners, and during the last years of his football career he doubled as assistant coach at the West Derby Golf Club. He moved for a spell to Rhodesia and then returned to Johannesburg to work as a golf pro while coaching various premier league soccer teams, including Southern Suburbs and his old club, Germiston Callies. Nivvy was also a very talented tennis player. King Gustav VI of Sweden once sent an aircraft to the UK to fetch the South African for a knock-up on the royal courts. Nivvy also scouted for talent in England as was reported by the Daily Mirror in July 1959: “Instant suspension faces any Soccer stars accepting offers from a South African agent, who plans a talent swoop in Britain. In a warning letter to the clubs the FA have revealed that the agent is Berry “Nivvy” Nieuwenhuys, former Liverpool winger, who now coaches in Johannesburg. Acting for the Transvaal Professional League – a newly formed rebel outfit not affiliated to the South African FA – Nieuwenhuys will approach players here with big money contracts, a job outside football and free passage to South Africa. But stern action faces any who accept. They would be blacklisted automatically by the FA, and any body associated to FIFA, the international controllers.”

| Weight | N/A |

|---|